The Rent vs Own Decision For Retirement (New Zealand)

Let’s talk about spending - because that’s the real topic of discussion underneath the rent vs own debate in Retirement.

Most people picture retirement planning as “how much do I need?” but the practical version is simpler. It’s:

“How do I convert the savings I’ve built into a stable, livable weekly lifestyle for as long as I’m alive?”

A common ideal should then be to spend confidently throughout retirement and arrive at the end having used up every single dollar for its purpose. Not to die with the biggest balance, but to match money to life.

So in this post, we’re going to model the same retiree under a few housing systems:

Rent and invest the $1,000,000

Buy a home and live off what’s left

Move into a retirement village and live off what’s left

The assumptions in this case study

A single person retiring at 65

They’ve sold their previous home and are entering retirement with $1,000,000

Investments are held in a balanced portfolio

NZ Super is included as retirement income ($28,000 per year / $538 per week)

Costs rise with inflation in the background at 3% per year (unless stated otherwise)

Important: these are projections, not promises. The value is derived from seeing what drives outcomes.

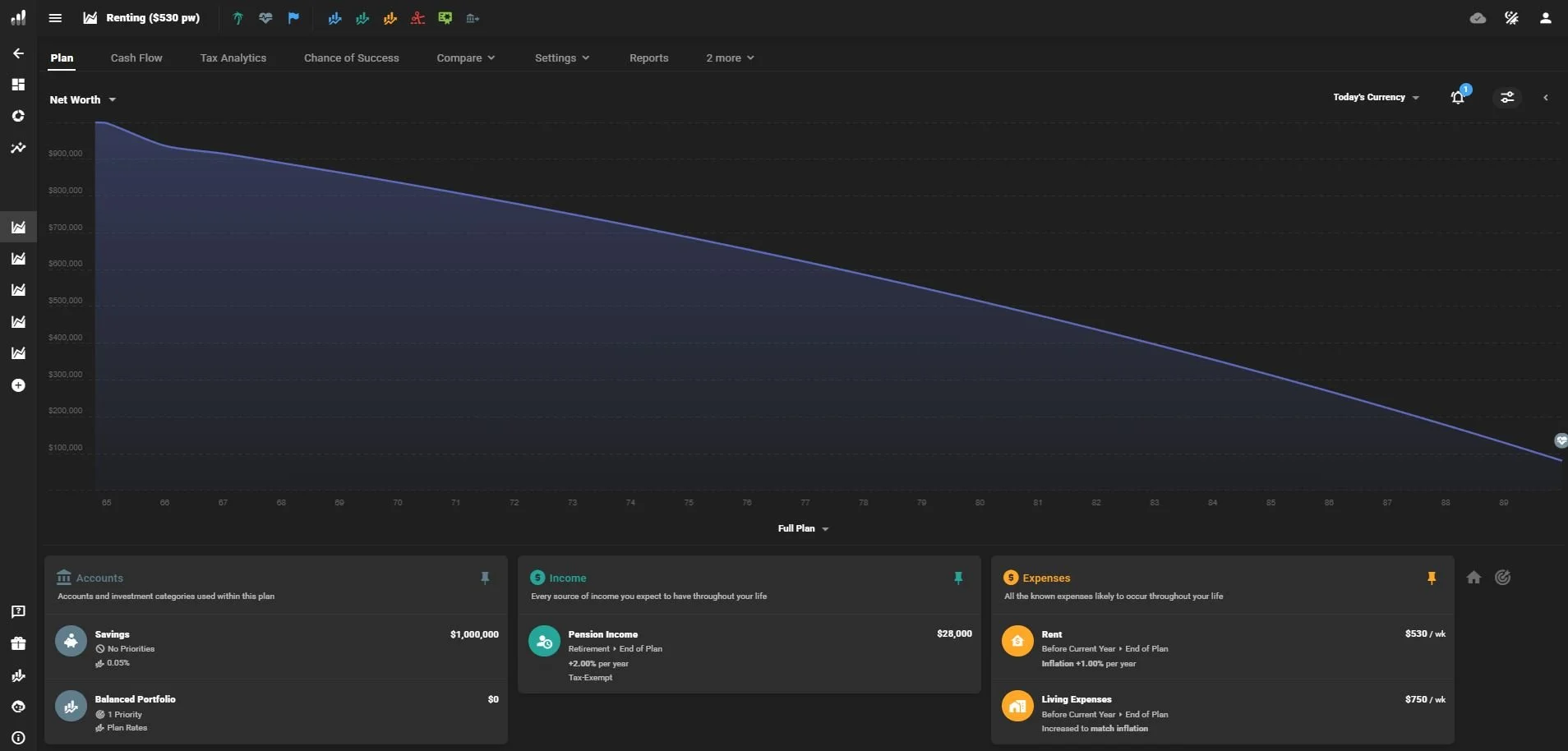

Rent A Home ($530 per Week)

This projection models a retiree starting with $1,000,000 invested in a balanced portfolio, renting at $530 per week and spending $750 per week on living costs (in today’s dollars). To add a buffer of safety we are projecting rent rises at 4% per year (CPI + 1%) - which is faster than the norm of 2%-3% per year.

In this scenario, the retiree keeps the full $1,000,000 invested and rents a home at $530 per week.

They then draw additional spending for living costs - food, transport, health, power, hobbies, and day-to-day life - at $750 per week.

What this chart is really showing is the cost of keeping housing as a permanent line item.

When you rent in retirement, you are choosing to fund housing from the portfolio every year, forever. That creates two pressures:

Your withdrawals are higher

Higher withdrawals mean the portfolio has less time to compound - and you’re more exposed to poor returns early on.You’re exposed to rent inflation

Even if inflation is “normal”, rent can move faster than the general CPI basket. A plan that works at $530 per week can stop working if rent resets upward.

The upside of renting is flexibility and liquidity:

You keep your capital invested

You can move suburbs, cities, or downsize easily

You don’t have homeowner maintenance surprises

The downside is that you never actually solve housing. You simply keep paying for it.

Key risks of renting:

Rent increases faster than modelled, especially during tight rental markets

You may have to move multiple times in retirement due to landlord decisions, sale of property, or tenancy changes

Longer life expectancy increases the chance you face a difficult period of markets and rent increases at the same time

Health changes can force a move into more suitable housing that costs more

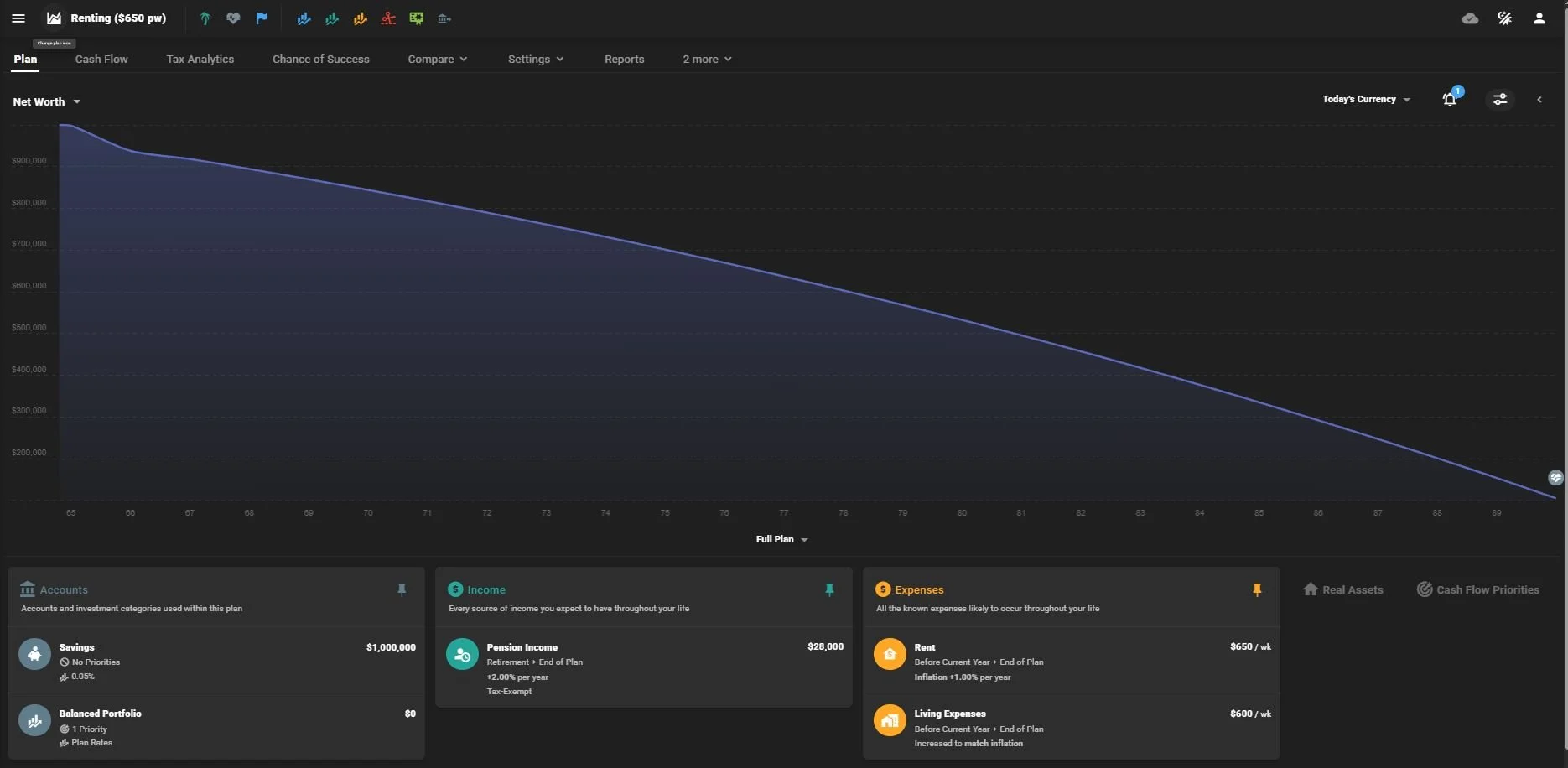

Rent A Home ($650 per Week)

Same setup - $1,000,000 invested in a balanced portfolio - but rent increases to $650 per week. To keep the plan workable, living expenses are reduced to $600 per week, highlighting the real trade off: higher rent doesn’t just reduce the ending balance - it reduces lifestyle, year after year. In this projection we’re assuming rent rises materially faster than long term expectations of 3% per year.

And this is the key lesson:

Higher rent doesn’t just cost you more, it reduces standard of living.

Most retirees experience higher rent as:

fewer holidays

less buffer for health

delaying dental

driving the same car longer

saying no to hobbies and social spending

Rent is a lifestyle lever. And in retirement, lifestyle levers matter more than the net worth number.

Key risks of renting at higher levels

The plan becomes more fragile - there is less “fat” in the budget for lifestyle spending

If health costs rise, there is nowhere easy to cut without reducing quality of life

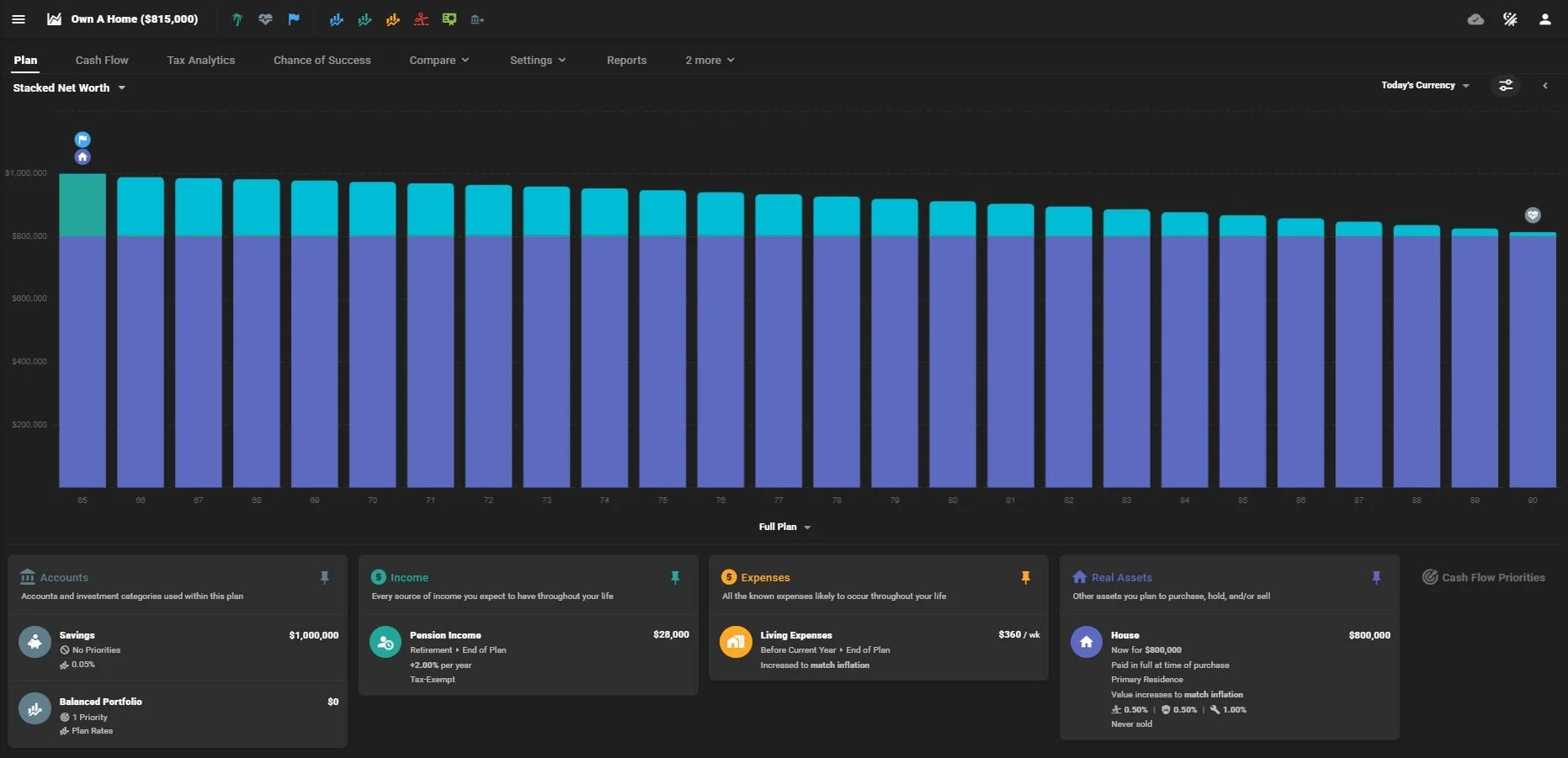

Buy A Home ($800,000) & Live Off The Rest ($200,000)

This scenario allocates $800,000 to a home purchase, leaving $200,000 invested to fund retirement spending. The chart looks stable because most wealth is now tied up in the house - but the key constraint becomes liquidity (in other words, you can’t eat the house): you still need to cover rates, insurance, maintenance, and day-to-day living from a much smaller investment pool.

This scenario is where most people feel emotionally safe - because owning a home feels like security.

And to be fair, it is a form of security.

But it changes what your $1,000,000 actually is.

Instead of $1,000,000 invested and liquid, you now have:

About $800,000 tied up in home equity

About $200,000 left invested to fund your lifestyle

This is where many retirees get surprised.

A home does not generate cashflow. It reduces one line item (rent), but introduces new ones:

Rates

Insurance

Maintenance and repairs

Long-term capital expenses (roof, repainting, appliances, bathrooms, fencing, drainage, damp)

In this example, we include:

$8,000 per year maintenance

$2,000 per year insurance

$4,000 per year rates

That’s $14,000 per year of “housing costs” that still exist, even when you own.

So the risk is not that owning is bad.

The risk is liquidity.

Net worth can look great on paper, but net worth doesn’t pay the grocery bill. Cashflow does.

If the remaining investments are only $200,000, your weekly spending ability becomes very tight (less than NZ Super yields) - because you’re asking a small pool of money to fund all living costs, for decades, while still absorbing homeowner costs.

This is where people end up on the peas and beans diet.

Key risks (Owning a higher-value home)

Asset rich, cash poor: a high net worth but limited liquid funds to live off

Maintenance is lumpy, not smooth - skipping it creates bigger bills later

Rates and insurance can rise faster than inflation

If health declines, you may need to pay for support and care while still holding an expensive property

The plan can force a late-life sale, which is emotionally and practically harder in your 80s

A quick counterpoint to consider:

It is possible to ‘eat the house’ using a reverse equity mortgage via a specialist lender (contact us for details), however, this lending usually comes with a much higher interest rate (I’ve seen around 8% per year) and may not be available throughout retirement. You’re then feeding two beasts at once: the amount you need to spend via borrowing against the value of the home, say $300 per week ($15,600 per year), then the interest on top (say at 8% pa, $1,248 for the first year and increasing as the loan grows from there).

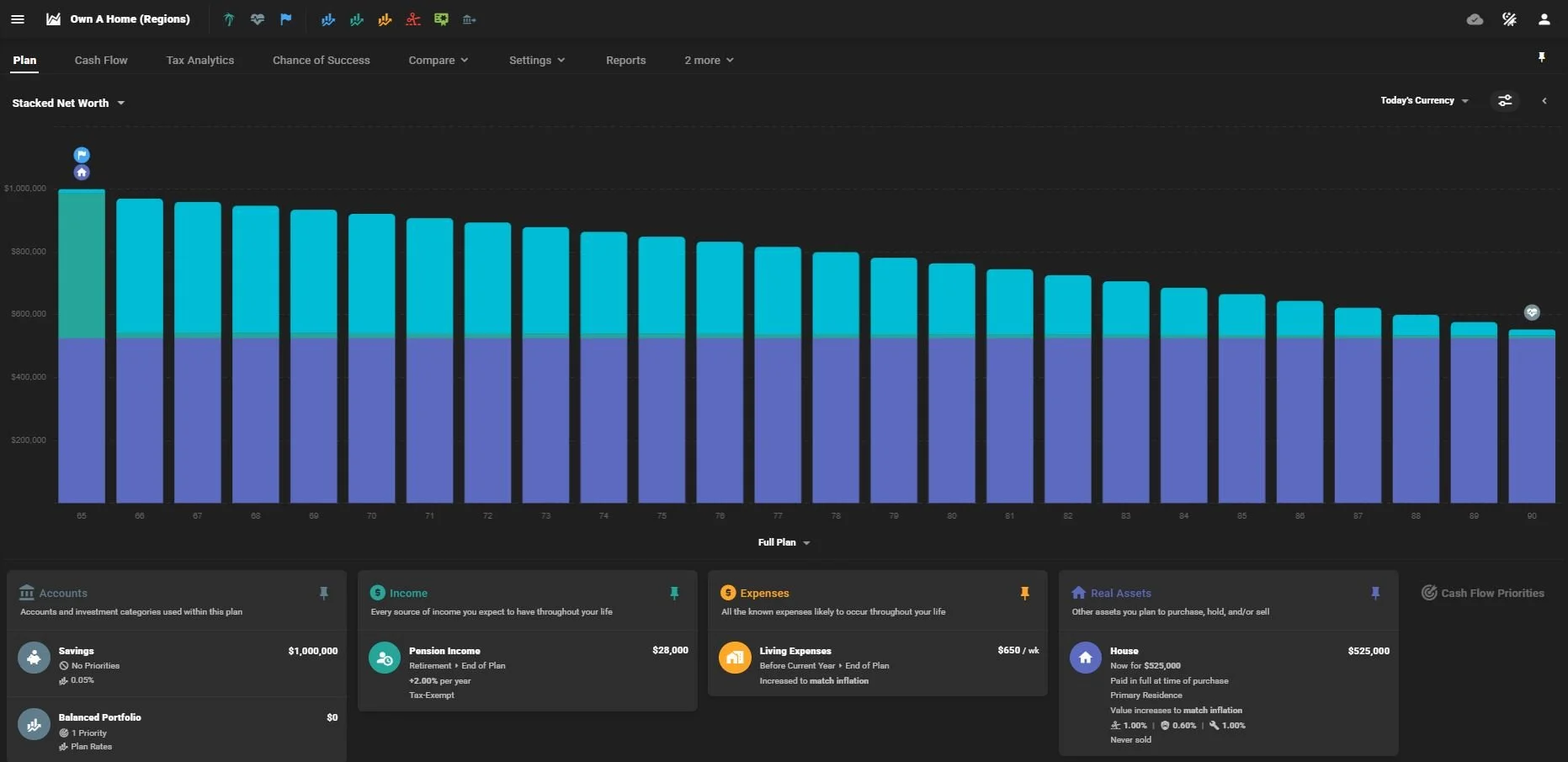

Buy in the Regions ($525,000) & Live Off The Remaining ($475,000)

Here the retiree buys a lower cost home ($525,000), preserving $475,000 invested to support lifestyle. The main advantage isn’t just “cheaper housing” - it’s flexibility: more liquid investments means more buffer for health costs, travel, car replacement, and surprises, without needing to sell the home later under pressure or accessing a reverse equity mortgage.

This scenario is the “same idea, better structure.”

You still get the benefit of owning:

less rent risk

greater housing stability

a home that matches inflation long term

But you keep far more liquidity:

You have meaningful investments left to fund your lifestyle

You can absorb health costs, vehicle replacement, and surprise expenses

Your plan has flexibility, not just survival

This is the piece most people miss:

Downsizing is not just cheaper housing - it is buying back optionality.

Optionality means:

you can fund care if you need it

you can travel while you’re able

you can replace things without fear

you can help family without sacrificing your own security

Key risks (Buying cheaper)

Lifestyle trade-off: you may be away from friends, family, and medical networks (importantly, most I’ve observed make this choice do end up moving back within 5 years to be closer to family being worse off real estate fees and moving costs)

Access to services: some regions have weaker health and support infrastructure

Emotional cost: the “cheaper home” has to still feel like a good life, not a compromise you resent

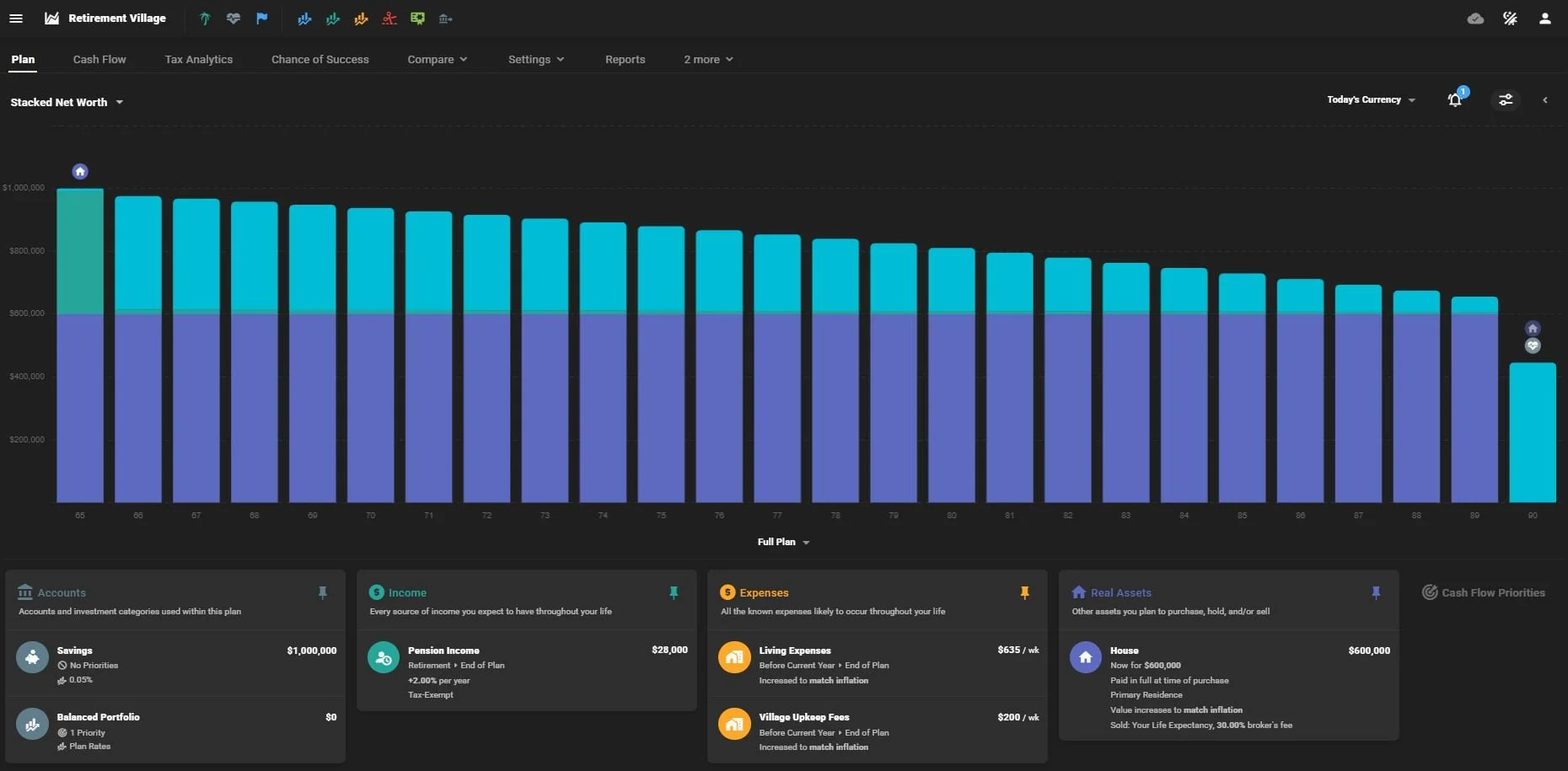

Retirement Village ($600,000) & Live off Remainder ($400,000)

This scenario pays $600,000 for a retirement village licence to occupy and keeps $400,000 invested for lifestyle spending. Ongoing village fees behave like a form of rent, and the long-term result depends heavily on the contract - fees, escalation, and how much capital is returned when you exit.

Retirement villages sit between renting and owning.

You pay a large upfront amount to secure a licence to occupy, then you pay ongoing village fees that resemble a reduced form of rent.

Financially, there are three moving parts:

The upfront capital amount

In this scenario, $600,000 is allocated to the village.The ongoing fees

Here the village upkeep is included as a regular expense - these fees can rise, and they are not optional.What happens when you leave

This is the part people often ignore.

Depending on the contract, the amount returned to your estate can be reduced by:

deferred management fees (25-30% of the value of the property)

time delays in repayment which occurs when they can’t find another buyer

refurbishment costs

resale costs

So the village can work well if:

you value support, community, and lower personal maintenance burden

you are comfortable with the fee structure

your family understands what the estate outcome is likely to be

But it can be detrimental if:

fees rise faster than expected

you need care that is more expensive than anticipated

the exit value is materially less than people assume

Key risks of retirement villages

Contract structure risk: what you get back can be far less than what you pay in

Note: this is especially important if you leave for another retirement village or external care center where you may pay the Deferred Maintenance Fee and perhaps be unable to afford to buy back in another center.

Fee escalation risk: weekly fees can rise faster than CPI

Care escalation risk: health changes can increase costs sharply later in life

Liquidity risk: you have $400,000 to fund lifestyle, but that pool must last and also cover unexpected health events

So what’s the actual takeaway?

It’s not that renting is bad or owning is good.

It’s that each housing option is a different cashflow system.

Renting:

Maximum liquidity

Maximum exposure to rent inflation

Housing remains a permanent annual cost

Housing may become unreliable in the long term as you may need to move a number of times

Owning:

Minimum rent risk

Higher stability

But there’s a risk of being asset rich and cash poor

Owning cheaper:

Keeps stability and reduces rent risk

Preserves the liquidity that funds lifestyle

Often the strongest “balance” outcome if the lifestyle works

Retirement village:

Lifestyle and support benefits

Ongoing fee structure plus contract complexity

Outcome depends heavily on the fine print

The best retirement plan is the one that still works when life gets messy

Most retirees don’t fail because the plan was wrong on day one.

They fail because something changes:

rent rises faster than expected

markets have a bad early decade

health declines

a partner dies

care becomes necessary

the home needs major repairs at the wrong time

The goal is not the prettiest chart.

The goal is resilience - and a lifestyle you can actually live with.